For millennia, empires have risen and fallen, some leaving behind monumental legacies like Rome, others vanishing almost without a trace, save for a carved city in the desert, like the Nabateans of Petra. Their lifespans vary, from fleeting to dynastic generations to centuries of dominance, but all eventually succumb to the forces of change, whether from external pressures or internal decay. In this grand historical sweep, we can view the traditional, centrally driven banking system, with its relatively brief history of a few hundred years — in “empire-speak” — as another dynasty on which the sun is setting. Its decline is a natural progression. Old ways, legacy systems, and inadequately updated technologies are being inexorably replaced, and indeed surpassed, by a new, AI-driven, egalitarian, and democratized financial ecosystem. The world turns, and as it does, the dawn of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, marks the sunset of the traditional, centralized, global banking dynasty.

The Legacy System: An Empire’s Fading Glory

The global financial system, long anchored by traditional banking institutions, often projects an aura of impenetrable stability and sophisticated efficiency. The tallest buildings. The biggest signs. The largest advertising campaigns. The pervasive involvement in all financial transactions. Yet, beneath the polished, monolithic exterior, lies a structure that is inherently vulnerable, shrouded in secrecy, for many, systemically unfair, and decreasing in relevance. This intricate edifice, meticulously built upon layers of traditional trust, amplified by legislated leverage, and complicated by complex financial instruments, is very much like the proverbial, precarious, “deck of cards.” Meaning, its stability is not absolute, but rather it is contingent on the unwavering confidence of its participants – a confidence that, if collectively withdrawn, could see the entire structure topple, rendering even the notion of “too big to fail” a tragic misnomer.

A defining characteristic of this fading empire is its pervasive opaqueness. Unlike a transparent public record, the inner workings of banks remain largely hidden. While regulatory bodies mandate periodic disclosures, such as quarterly “Call Reports” in the United States or compliance reports under international frameworks like Basel III, these are, by their very nature, selective and delayed snapshots, not real-time, comprehensive insights.

A bank’s true financial health, its dynamic risk exposures, and the intricate web of its interbank liabilities can shift dramatically between reporting cycles. For the ordinary depositor or even a keen market observer, understanding the granular details of a bank’s loan portfolio, its derivative positions, or its precise liquidity buffers remains an elusive task. This inherent information asymmetry means that insiders and regulators possess a far more timely and detailed understanding of the system’s vulnerabilities than the general public, leaving ordinary citizens vulnerable and often the last to know when trouble brews.

Even more important than the vulnerability of the system is the banking exclusion zone that keeps the “owners” of the money, in the dark. This lack of immediate transparency is a hallmark of an older era, ill-suited for a world demanding instant information and accountability.

A defining characteristic of this fading empire is its pervasive opaqueness. Unlike a transparent public record, the inner workings of banks remain largely hidden. While regulatory bodies mandate periodic disclosures, such as quarterly “Call Reports” in the United States or compliance reports under international frameworks like Basel III, these are, by their very nature, selective and delayed snapshots, not real-time, comprehensive insights.

The Concept of “Empire” in Traditional Banking

The modern concept of banking, particularly the institutional and central banking structures that underpin it, has roots in the great trading companies and nation-state empires of the last 300-400 years. The rise of institutions like the Bank of England in the late 17th century was intrinsically linked to managing government debt and financing military expeditions and colonial expansion, not to providing personal checking accounts.

Early banking was essentially a tool for powerful entities—governments, merchants, and joint-stock companies like the East India Company—to facilitate large-scale international trade, manage risk, and accumulate capital for grand projects. The systems and regulations that evolved from this era were designed to serve these ends. The “average person” was, for a long time, an afterthought, with their financial needs being met by local moneylenders or simple credit systems, or not met at all, but in any event, far removed from the complex, international machinery of high finance.

Alexander Hamilton’s introduction of a national banking system to the United States fits squarely within the narrative of the “Fading Empire.” His creation of the First Bank of the United States was not an effort to serve the personal financial needs of the average citizen. Instead, it was a strategic, centralized tool designed to solidify the new nation’s power, manage its colossal war debts, establish a stable currency, and facilitate large-scale commerce. This top-down, nation-building approach to finance is a perfect example of the “rigid and aging” power structure that prioritize’s the state’s and merchants’ needs over those of the individual.

Retail Banking is an Afterthought

The shift towards what we know as retail banking—mortgages, car loans, personal accounts, credit cards—is a relatively recent development, a product of the 20th-century consumer economy. However, the core architecture of the system still reflects its imperial, trade-focused origins. This can lead to a feeling of disconnect, where the individual’s experience of banking (paying bills, saving for a home) feels like a small, isolated part of a much larger, more opaque system designed for a different purpose entirely.

This “imperial” versus “retail” concept of banking directly mirrors the theme of this article, wherein the “fading empire” of traditional finance can be better understood as a complex, teetering “deck of cards.” The fragile, intricate, and sometimes opaque nature of the system is a direct legacy of its historical purpose. The rise of a new, decentralized, and AI-driven financial world, can be seen as a direct and antithetical response to this historical legacy. There is a new system, being built from the ground up, that is more egalitarian, completely transparent and immutable … that directly serves the individual.

Whose Money Is It Anyway?

As of 2025, the total of retail deposits in the US, banks and credit unions, is approaching $USD20 trillion. Globally, the number is hard to assess but it is probably in the region of $60-$70 trillion (of USD equivalents). Not much from that aggregate goes back into the pockets of the ordinary folks who park their dollars in those places.

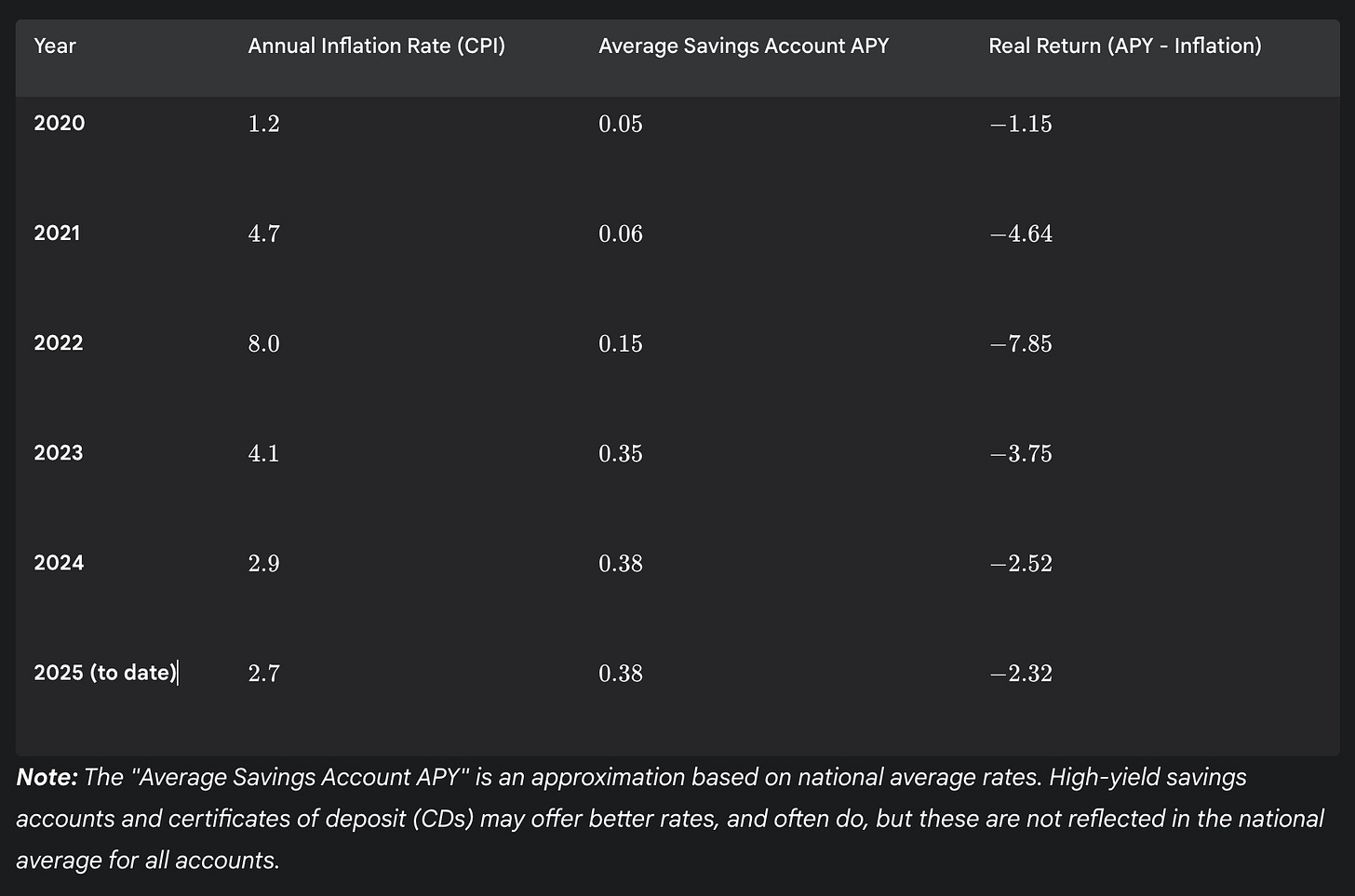

When compared to the inflation rate over the past five years, American depositors are actually losing not increasing their money each year. Depending on the year — they are going backwards: -1.15% (2020), -4.64% (2021), -7.85% (2022), -3.75% (2023), -2.52% (2024), and -2.32% (2025 YTD).1

Now, the other side of the story: If a small, local bank holds $100 million in core deposits, it pays a relatively low price for this funding, roughly 1%-2% per year. The bank leverages these cheap, core deposits to create new loans, which in turn creates new money. By maintaining a profitable spread—earning interest on the larger volume of loans and generating a healthy Net Interest Margin (NIM)2—while paying less on its deposits, the bank expects to generate significant fee income. An average-performing $100 million bank is making about $10 million (ROE: return on equity), while a well performing bank might be making as much as $15 million to $20 million ROE for its shareholders. The depositors have zero say in how this process unfolds and no right to share in the bank’s profits from creating and putting that money to work.

The opaqueness — even secrecy — of banking is further exacerbated by the fundamental mechanism underpinning traditional banking: fractional reserve lending.

Banks are permitted to lend out a substantial multiple (usually 10x) of the deposits they hold, effectively creating new money and credit within the economy. While this process is historically lauded as essential for economic growth and capital allocation, it simultaneously introduces an inherent and significant degree of leverage. That is the deck of cards; a ten-story building without a foundation.

For every dollar a depositor entrusts to a bank, the institution can, through successive lending cycles, generate many more dollars in loans, investments, and fees. The profits derived from this multiplication of capital accrue overwhelmingly to the bank, while the ordinary depositor often receives a paltry return on their savings, frequently yielding less than the rate of inflation.

If the depositors choose to go elsewhere, en masse, perhaps seeking a fairer share of the value their money creates, perhaps just seeking more transparent control of their money, there is no foundation underpinning the tall structure. This instability is obviously true for individual banks. Collapses or disappearances happen all the time — in the US at the rate of hundreds of banking institutions per year.

In large measure the smaller banks (and credit unions) are being absorbed into larger ones, which simply means that the same foundational / systemic issues are being compounded into a smaller number of institutions.3

Usury

In another twist, the stark disparity of deposits/earnings invites a provocative, yet historically resonant, discussion around the concept of usury. While modern legal frameworks have normalized interest-bearing loans, the moral and societal implications of a system where the financial institution earns a 10x multiple on pooled capital, while the original capital providers receive a fraction, raises questions about systemic fairness (not to mention the disgusting practices of check cashing / payday loans and other supposedly short term lending businesses4).

This “normal,” “business as usual” lending practice means that the very design of traditional banking concentrates wealth and power, which is inherently alienating or exploitative for those outside its inner circle.

In Mere Christianity, author C.S. Lewis addresses the traditional Christian view on usury (lending money at interest), highlighting a historical consensus against it among ancient Greeks, Jews, and medieval Christians. He acknowledges that the modern economic system is built upon lending at interest, but raises the question of whether this modern practice contradicts the long-standing moral prohibition.

Given that usury is a forbidden practice in the various forms of canonized scripture, and a sacrosanct rule of law for many civilizations spread across thousands of years, how is that the modern world has come to not only condone usury, but to embrace it, and become totally reliant upon it? The inherent flaws and obvious disparities in the financial system, which hinges entirely on an aggressive (egregious) form of usury, is another reason to suggest that this empire’s days are a phase in the passage of time, not something to cling to beyond its “use by date.”

Given that usury is a forbidden practice in the various forms of canonized scripture, and a sacrosanct rule of law for many civilizations spread across thousands of years, how is that the modern world has come to not only condone usury, but to embrace it, and become totally reliant upon it?

Derivatives

Adding another layer of precariousness to this “deck of cards” is the pervasive use of derivatives. These complex financial instruments, whose value is derived from underlying assets, not direct ownership in the assets, allow institutions to take on enormous exposures with minimal upfront capital. While intended for hedging and risk management, their speculative application can amplify both gains and losses to staggering proportions.

The true danger lies in the intricate, often hidden, web of counterparty risk they create across the global financial landscape. A default by one major participant on a derivative contract can trigger a cascade of failures, as interconnected institutions face sudden liquidity demands and solvency crises. The opaqueness surrounding these derivative positions means that the full extent of the system’s interconnected leverage is rarely understood until a crisis erupts. The “deck of cards” is incredibly fragile, with hidden threads connecting many seemingly disparate elements.

Moribund Movement of Money

Beyond these structural vulnerabilities, traditional banking imposes tangible and often prohibitive cost and time constrictions on the movement of people’s own money. Domestic transfers can take a business day or more to clear, while international remittances, crucial for migrant workers and global commerce, are notoriously expensive and slow. Wire transfer fees can range from $35 to $65 for outgoing international payments, with additional, often hidden, costs embedded in unfavorable currency exchange rates. The global average cost for sending a $200 remittance still hovers above 6%, with traditional banks often charging over 12%. These fees disproportionately burden lower-income individuals sending vital funds to their families. Furthermore, the reliance on intermediary banks, disparate business hours across time zones, and batch processing mean that international transfers often take days to settle (typically 1-5 business days via SWIFT or its alternatives5), leaving senders and recipients in limbo with little real-time tracking. This friction is not merely an inconvenience; it acts as a significant barrier to financial inclusion and economic participation for billions worldwide, marking traditional finance as a system with inadequately updated technologies in a rapidly accelerating world.

Is it a Party if No One Comes?

Ultimately, the traditional banking system’s greatest vulnerability, and the essence of the “deck of cards” metaphor, lies in its absolute reliance on confidence. The notion of “too big to fail” is not a testament to the system’s robustness, but rather a chilling admission of its fragility. It signifies that certain institutions are so deeply interwoven into the financial fabric that their collapse would trigger a catastrophic systemic failure, necessitating government intervention and taxpayer-funded bailouts. However, this implicit guarantee only holds as long as the fundamental “card” of public confidence remains in place. If consumers and businesses, en masse, were to collectively and irrevocably remove their confidence from the system—perhaps due to a perceived lack of transparency, persistent unfairness, or a fundamental loss of trust in its integrity—or even more likely, migration to a better way—the entire edifice would — will — inevitably crumble.

In such a scenario, “too big to fail” would indeed become an incorrect term, as no amount of government intervention could prop up a system whose foundational element, collective belief, had been decisively withdrawn.

Can the Banking System Withstand the Light of Day? Confidentiality vs. Secrecy

Confidentiality and secrecy, though often used interchangeably, operate on fundamentally different ethical principles. Confidentiality is the purposeful and ethical act of protecting sensitive information, governed by mutual trust, clear boundaries, and a justifiable reason for its protection—such as the legal and medical privileges that safeguard vulnerable individuals. It implies a shared understanding and is maintained with a legitimate purpose in mind. Secrecy, on the other hand, is the act of concealing information without a clear or ethical justification, often serving to protect a hidden agenda, exert control, or hide wrongdoing. While confidentiality builds trust and is, by nature, transparent in its intent, secrecy erodes trust by creating an opaque wall designed to prevent accountability and scrutiny. A system built on confidentiality can be audited and its justifications understood; a system built on secrecy, however, is inherently fragile, for its very existence depends on the suppression of truth. Can a system that operates in the darkness of secrecy withstand being exposed to the light? The conclusion to that question is becoming self-evident.

Banking as a Class System

The legacy financial system, in this context, has historically operated with a structural form of secrecy, particularly regarding its inaccessibility to the world’s most vulnerable. By design, the traditional banking model has tended to exclude those with less, especially in the Global South, creating an unintended yet formidable class system. Its complex requirements for collateral, documentation, and minimum balances have effectively served as a barrier to entry, simultaneously helping to protect the dynastically wealthy by limiting competition and maintaining the status quo. Because of its antiquated structures and centralized technologies, the traditional banking system has proven to be too rigid to adapt meaningfully for the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum, offering little more than basic, low-interest deposit services, which only reinforces the very power dynamics it was designed to serve.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution: Forging an Egalitarian Financial Ecosystem

This is precisely where blockchain technology emerges as a compelling counter-narrative, offering a fundamentally different paradigm for finance that is perfectly aligned with the principles of the Fourth Industrial Revolution — 4IR — a fusion of technologies blurring the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres.

At its core, blockchain is an open and immutable distributed ledger. Every transaction is publicly verifiable and cryptographically secured, creating a tamper-proof history that is accessible to all. This inherent transparency eliminates the information asymmetry that plagues traditional banking, providing real-time visibility into the flow of value and the state of assets. There are no hidden books or delayed reports; the ledger is continuously updated and broadcast to all participants. This cryptographic certainty and universal accessibility foster trust through verification, rather than through reliance on centralized intermediaries.

Moreover, blockchain directly addresses the high costs and time delays of traditional money movement. Through peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions, value can be transferred directly between individuals and businesses without the need for multiple intermediary banks, drastically reducing fees and accelerating settlement times to minutes or even seconds.

The blockchain operates 24/7/365, unconstrained by banking hours or national holidays. While native cryptocurrencies can be volatile, the advent of stablecoins (digital assets pegged 1:1 to individual fiat currencies or baskets thereof or other stable assets) provides the best of both worlds: the speed and low cost of blockchain with the stability required for everyday transactions and remittances.

Furthermore, the growth of Decentralized Finance (DeFi) protocols, powered by smart contracts, allows for permissionless financial services like lending, borrowing, and trading directly on the blockchain, potentially offering more equitable returns to participants by cutting out traditional intermediaries.

Continuous innovation enhances scalability, reduces transaction costs, and increases throughput, making blockchain-based payments even more viable for global mass adoption.

Crucially, this emerging financial landscape is not just decentralized, but increasingly AI-driven. Artificial intelligence is and will significantly enhance the efficiency, security, and accessibility of this emerging ecosystem. AI algorithms can be deployed for real-time fraud detection on public ledgers, optimize transaction routing on busy networks, provide personalized financial insights and automated investment strategies for individuals, and even improve the efficiency of decentralized governance mechanisms.

By analyzing vast datasets of on-chain activity, AI can identify patterns, predict market movements, and enhance the overall user experience within a decentralized framework, without reintroducing the centralizing forces of traditional finance. This integration of AI with blockchain creates a truly egalitarian and democratized financial ecosystem, where access is permissionless, costs are minimal, and the benefits of financial innovation are distributed more broadly among participants, rather than being concentrated in the hands of a few large institutions.

The Pragmatic Shift: From a Fading Empire to a New Frontier

Inevitably, the vestigial guardians of old kingdoms engage in sometimes nefarious politicking, intrigue, and elaborate defence machinations. It always was thus. The Machiavellian principles of The Prince are still extant in many halls of power.

Even so, the transition from the old, centrally driven banking system to this new, distributed, and AI-enhanced financial ecosystem is driven by practical, pragmatic and ultimately irresistible forces in a rapidly changing world.

The traditional system, with its inherent opaqueness, extensive leverage, and cumbersome money movement, are simply becoming too inefficient and grossly inadequate for the demands of the digital age.

Just as ancient empires eventually yielded to more adaptable and efficient forms of governance and technology, so too is the financial world witnessing a natural decline of an outdated model. While large banking houses have historically benefited from and perpetuated this structure, the shift is now driven by technological superiority and a growing global demand for transparency, fairness, and efficiency.

The inefficiencies and costs that were once accepted are now being exposed and surpassed by blockchain’s inherent design.

As the world fully enters the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the fusion of digital, physical, and biological technologies demands financial infrastructure that is equally agile, transparent, and inclusive. The “deck of cards” of traditional finance, while historically dominant, is gradually being rendered obsolete by a more robust, open, and democratized alternative.

This is not about dismantling the old, but rather about the rapid evolution of a superior new, AI-driven financial reality that is inherently more resilient, accessible, and aligned with the demands of a globally interconnected and digitally empowered populace.

The future of finance is not just evolving; it is being fundamentally re-architected, card-by-transparent-immutable-card, as the sun sets on one financial era and rises on another. §

Author’s Note: Some of my best friends are bankers. I am still an active and supportive contributor to the United States Bankers Association (USBA / usbankers.org). I have spent more than 40 years working with some of the biggest and some of the smallest of banks in the world. The above reflections bear no element of animus; banking in general has been my friend, professionally speaking. However, it would also be quite true to say that there is a bank involved somewhere in the flow — a financial transaction of some kind — uplifting and enabling the very best things happening on this planet, and the very worst, most sordid elements of human behavior. Banking is not the culprit or the hero, it is just a tool. As Apostle Paul noted, it is not money — the tool — that ever performs evil, it is the love of money (see 1 Timothy 6:10) — it is the human intent that decides to what work the tool will be applied. Likewise, the above is not about heroes or villains, it is simply an informed observation about what has been and what is. Still, I do celebrate the more inclusive nature of the systems that are rapidly evolving. Jesus Christ said that the poor will always be with us (see Matthew 26:11), but anything we do collectively to advance the cause of human flourishing, that means there will be less poor, and more abundance, so much the better.

Epilogue: It’s a Must: Greater Financial Literacy is Needed to Foster the Most Inclusive DeFi Ecosystem

For decentralized finance (DeFi) to become a truly egalitarian and inclusive global financial ecosystem, a deliberate effort to foster financial literacy is critical. Without education, the benefits of these new technologies risk accumulating in the same hands as the traditional system. Veritas Chronicles will be looking for and reporting on those efforts which are attempting to level the playing field, globally. Here are a handful ideas with which we challenge creators to develop FiLi (financial literacy) to match and help fulfil the promise DeFi —

- Gamified Learning Platforms: Create interactive, game-like platforms that reward users with small amounts of cryptocurrency for completing modules on topics like wallets, smart contracts, and liquidity pools. This approach, similar to existing “Learn and Earn” programs, makes education engaging and provides a low-stakes environment for hands-on practice.

- AI-Powered Mentors: Develop AI tools that act as personalized financial mentors. These tools, accessible via simple interfaces and available in multiple local languages, could use large language models to explain complex DeFi concepts in an understandable way. They could also help users model different financial scenarios, such as the potential risks and rewards of staking or lending, without requiring them to put real money at risk.

- Community-Led Education: Empower local leaders and organizations in the Global South and other underserved communities to run their own education programs. These could be supported by decentralized grants or DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) that fund the creation and distribution of tailored educational materials, ensuring that the knowledge is culturally relevant and addresses the specific needs of each community. By making education a community-driven effort, it builds trust and creates a sustainable knowledge base that can spread organically.

- Risk-Free “DeFi Sandbox” Environments: Create simulated platforms or testnets where new users can experiment with DeFi protocols using play money. This “sandbox” would allow them to perform real-world actions—like providing liquidity, swapping tokens, or taking out a loan—without any fear of financial loss. This hands-on, no-consequences approach helps build practical confidence and muscle memory before a user ever has to touch a live blockchain with real funds.

- Decentralized Certifications and Badges: Create systems where individuals can earn on-chain credentials or non-fungible tokens (NFTs) for demonstrating mastery of various financial literacy topics. These verifiable badges would not only serve as a record of their knowledge but could also be integrated into DeFi protocols to grant access to special features, reduced fees, or exclusive airdrops. This creates a tangible, valuable incentive for learning and a new form of digital reputation that is entirely owned by the user.

Security token issuers could consider adding utility tokens to their offerings to some or all of the above financial literacy opportunities to (a) increase the uptake of their token offering as well as (b) achieving a massive and fundamentally critical social impact outcome.

↩︎

↩︎- Net Interest Margin (NIM) is a key profitability metric for banks. It measures the difference between the income a bank generates from its interest-earning assets (like loans) and the interest it pays out on its interest-bearing liabilities (like deposits), expressed as a percentage. A higher NIM generally indicates a more profitable and efficient bank. The formula is: NIM=(Interest Income Minus Interest Expense)÷Average Earning Assets ↩︎

- As of the end of 2023, there were approximately 4,596 chartered banks and 4,604 chartered credit unions in the USA, totaling around 9,200 depository institutions. More recent data from March 2025 indicates the number of credit unions has further declined to 4,411. The combined peak number of financial institutions in the U.S. occurred in different periods for banks and credit unions. The number of FDIC-insured financial institutions (banks) reached its peak of approximately 17,900 in 1984. The number of credit unions apexed earlier, in 1969, at 23,866. Both banks and credit unions have seen a significant decline in their numbers since their respective peaks, largely due to industry consolidation and failures over the decades. ↩︎

- Payday loans and check-cashing services often trap individuals in a cycle of debt. These businesses provide quick cash for a fee, but their high interest rates and fees can be exorbitant, sometimes translating to an annual percentage rate (APR) of over 400%. This is a blight on communities because it disproportionately affects low-income individuals who may not have access to traditional banking services. These predatory lending practices drain financial resources from vulnerable communities, making it incredibly difficult for people to escape poverty and build generational wealth. ↩︎

- There isn’t a single system currently replacing SWIFT, but rather several alternatives and upgrades are in development or have been launched to compete with it. SWIFT is also in the process of upgrading its own messaging standard to ISO 20022.

Here are some of the notable alternatives:

CIPS (Cross-Border Interbank Payment System): Developed by China, this system is designed to facilitate cross-border transactions in the Chinese yuan.

SPFS (System for Transfer of Financial Messages): This is Russia’s equivalent to SWIFT, developed in response to the threat of being disconnected from the SWIFT network.

BRICS Pay: An initiative by the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) to create an independent payment system for trade among members.

Blockchain and Cryptocurrency Platforms: Networks like RippleNet and the Bitcoin Lightning Network are being explored as decentralized, faster, and cheaper alternatives for cross-border payments.

These systems, along with others like SEPA (Single Euro Payments Area) in Europe and various real-time payment networks, are creating a more fragmented and competitive landscape for international financial messaging. ↩︎